Reading papers

Contents

Reading papers¶

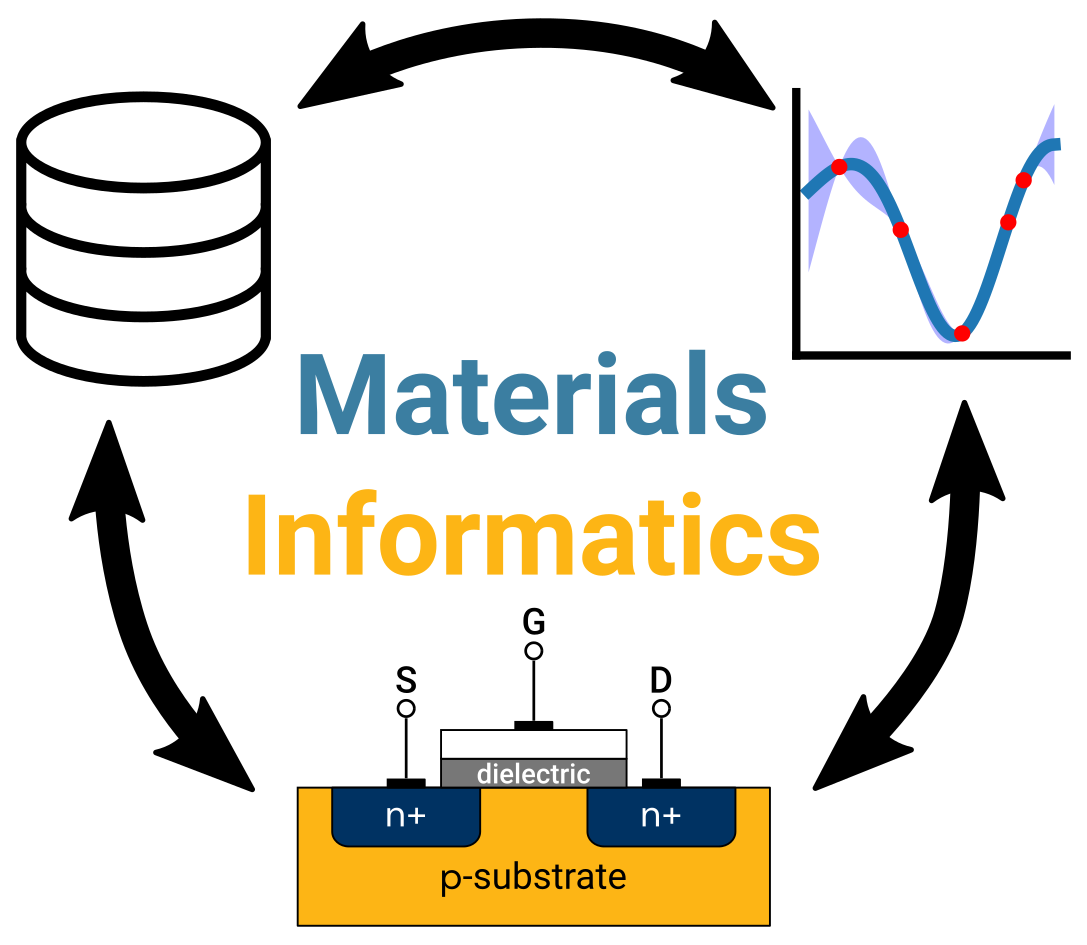

As was mentioned in the introduction to this module, MI is a relatively nascent field, and this means that a lot of the knowledge and methods are still being developed in the research side (and not much pedagogy has been established). Fortunately, this means that a lot of what we seek to learn has been documented in research papers; unfortunately, this means that to obtain that knowledge, we have to read research papers. 🤮 Reading papers is an important part of the research process, whether it’s brushing up on a topic, conducting a thorough literature review, etc., but it is a hard skill to master. So far, we’ve already had you read a few research papers and pointed out what to pay attention to, but what happens when you’re doing your own literature search? What if instead of one paper you suddenly have ten that you have to sift through for information? And wait a sec—how do we even find papers and access them? This document attempts to answer these questions.

How to read papers¶

There’s a lot of guidance out there on how to read a scientific research paper, such as one by S. Keshav that we’ve shared in the Drive [1]. We actually suggest you start with this document as it’s short (2 pages!) and we left a few comments on there. If you don’t like that advice, you can search for many more on Google.

Finding papers¶

There are many resources that you can use for finding papers, but for simplicity and generally-good results, we recommend you enter search queries on Google Scholar (different from Google search!). We’re all pretty familiar with how general Google search works, including its advanced search/filters, and this website has indexed essentially all of the relevant journals for our needs. If you’ve never used this platform before, we suggest you try it out with terms like “screening dielectric materials” or “materials informatics” and seeing what pops up. When you’re finding papers, enter keywords (doesn’t have to be a full sentence!) that describe what you’re looking for.

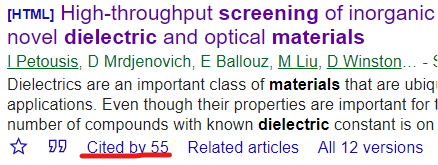

Another place to find relevant papers is in the list of references in a relevant paper that you have already read (or at least know of). This is because often times the paper you just read builds upon other work that could have a critical piece of information that you’re looking for, and you will know this association based on how the older paper was cited in the newer paper. Another cool feature of Google Scholar is their “Cited by” feature that accompanies every search result. This address the reverse problem, and finds all of the indexed papers that cite the article that’s listed.

Accessing papers¶

You’ve learned how to read papers, you’ve found the perfect paper you’ve been looking for, you’ve situated yourself in a comfortable reading environment, and then you realize: Wait, what? I can’t access this paper? It is the unfortunate truth that scientific publishing is a business, and this means articles published by organizations like Springer, ACS, AAAS, and many others keep articles behind a paywall and charge subscription fees for access. These fees can grow to be quite large and difficult for academic institutions to pay. If you haven’t already heard, check out UC Libraries’ tussle with publishing giant Elsevier. 🍵 In short, if you don’t have access to an article, you’ll only be able to see the title, authors, and the abstract.

Luckily, we have a few options available to us to access the full text. The first is that we might come across an article that is open access, which means that somewhere along the publishing pipeline, someone else paid or waived the fees so that anyone can read the published article for free. These individual articles will be clearly labeled as such on the official publisher’s website, and this is part of a broader “open science” movement. There are also a few sources, both official journals and pre-print servers, that have all open-access articles, including Nature Communications, npj Computational Materials, Scientific Data, Science Advances, PNAS, ACS Central Science, and arXiv. While these titles may not mean anything to you at the moment, they are definitely a blessing when you come across them. 🙏

The second option, which works for most articles that you come across, is to take advantage of the fact that we go to a great research institution like UC Berkeley that has already paid the subscription fee for us (the UCs as a whole have, technically). There are many ways to use your UC Berkeley credentials to access papers behind a paywall, but the simplest one we’ve found is to use the EZProxy bookmarklet. If you are unfamiliar with setting this up, please see this helpful video from UCB libraries.

References¶

- 1

S. Keshav. How to read a paper. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev., 37(3):83–84, 2007. doi:10.1145/1273445.1273458.